Editor’s Note

The author of this piece, Kevin Duska, has a long-standing affection for allegory, metaphor, and the grotesque elegance of systems in collapse. In this case, the metaphors are not just rhetorical devices — they’re coping mechanisms.

When confronting an institution like the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), whose structure, incentives, and public communications so profoundly betray the idea of “oversight,” the usual vocabulary of policy critique becomes insufficient. Dry prose doesn’t capture the heat. Or the stench.

This article, the first published on Atomic Kings, Canada’s only independent nuclear regulatory oversight watchdog, is not a conventional op-ed. It is a scalpel shaped like a middle finger — simultaneously flipping off the institution and reaching toward its prostate in a digital rectal exam that loops into infinite recursion. It is also — regrettably — a documentary reflection of the author’s ongoing experience navigating Canada’s federal access-to-information regime, including multiple Privacy Act requests and six Access to Information Act files currently open with CNSC. The tone was not chosen lightly. It is the byproduct of sustained institutional gaslighting, procedural evasion, and a bureaucratic allergy to transparency so severe it borders on the autoimmune.

Extraordinary institutional vulgarity demands extraordinary descriptive precision.

If you find this piece offensive, consider the possibility that it is describing something even more offensive — and doing so with restraint – or that you are indeed part of this human centipede.

In an ideal world, this article wouldn’t need to exist. In this one, the centipede walks among us. Some of you, dear readers, are its part – from mouth to anus – and that trajectory is both endless and inescapable.

I. Prologue – The Diagram They Won’t Show You in Ottawa

There’s a certain elegance to how regulatory capture works in Canada. It doesn’t crash through the door in a scandal. It doesn’t need to. It just quietly sets up a desk next to the regulator, hands it a press release, and lets the system call it “consultation.”

Nowhere is this more grotesquely embodied than in the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) — the federal agency tasked with overseeing nuclear safety. Or, more accurately, the front-facing mouthpiece of a system built to consume public trust and excrete regulatory approval.

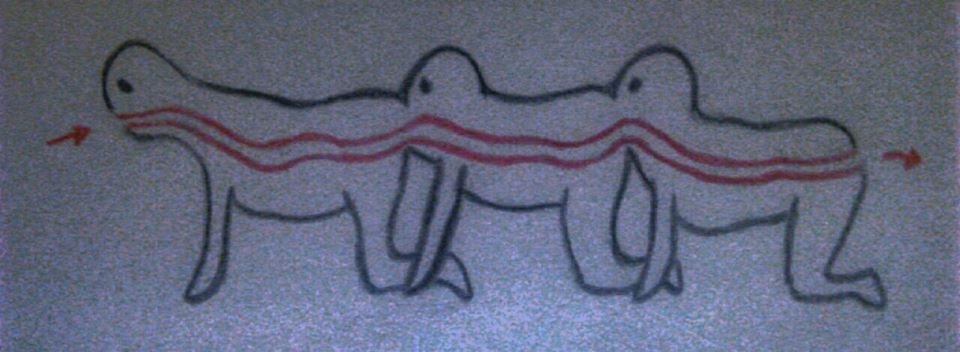

Welcome to the human centipede model of Canadian oversight: the CNSC stitched mouth-to-ass to industry, policy, and ministerial command, choking out sanitized reassurances while digesting everything fed in from the corporate back end. The result isn’t oversight — it’s a digestive process that converts complex public risk into pre-approved permits and PDF fact sheets.

The CNSC would like you to believe it operates independently. That its decisions are guided by science, safety, and solemn duty. But follow the tubes: it reports to the Minister of Natural Resources, whose job also includes promoting nuclear development. The same minister who benefits politically from new nuclear projects is the one filtering what comes out the other end of the CNSC.

The Near Surface Disposal Facility (NSDF) at Chalk River is the latest product of this system — a shallow radioactive landfill, greenlit with a straight face, built on unceded Indigenous land beside the Ottawa River. But it’s not just the dump that stinks. It’s the entire process that produced it.

This isn’t a hit piece. It’s a biopsy.

And what we’re looking at isn’t oversight.

It’s a slow-motion gastrointestinal collapse wearing a safety helmet.

II. Head of the Beast – The CNSC’s Faux-Independence

Let’s start at the head — the so-called “independent” Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission.

Independence is the branding. The reality is a structural joke that’s somehow still getting funnier in committee. The CNSC reports to Parliament through the Minister of Natural Resources — the same minister responsible for promoting nuclear development in Canada. That’s like asking the head of marketing to also run quality control, then acting surprised when the product explodes.

This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s public record. It’s just that no one wants to say it out loud because the implications are messy — and mess doesn’t suit Ottawa’s beige-on-beige décor. The International Atomic Energy Agency recommends a clear separation between nuclear regulators and promoters. Canada’s response? A polite shrug, “hold my Labatt,” and another round of funding announcements.

The CNSC’s leadership reinforces this confusion. Its president chairs meetings in the language of technical neutrality while greenlighting billion-dollar facilities cooked up by for-profit consortia with a direct line to the ministerial brass. Its commissioners cycle in from industry, academia, or the civil service — and somehow never, not once, from the communities living downstream of their decisions.

This isn’t oversight. It’s client service in a lab coat.

Pull up any CNSC announcement and count how many times they cite their commitment to “science-based decisions.” Now count how often they disclose that the science in question was provided by the contractors trying to get the damn thing built. Spoiler: you won’t. Because admitting that would mean the science isn’t neutral — it’s curated.

In the Chalk River case, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) provided the data. The CNSC reviewed it and gave it the stamp. The fact that CNL stands to profit massively from that approval? Not relevant. Apparently.

Meanwhile, Indigenous communities like Kebaowek First Nation filed detailed, urgent submissions opposing the project. The CNSC thanked them for their engagement — then buried the feedback in an appendix and moved forward anyway.

This is the part of the centipede where the face smiles for the camera while the rest of the system quietly absorbs whatever’s being shoveled in behind it. The CNSC’s mouth says “safety.” The rest of its body says, “keep it moving.”

If you think this is just bureaucratic awkwardness, think again. This setup isn’t broken. It’s functioning exactly as intended.

Because in Canada, independence means you can speak without thinking —

as long as someone else is feeding you the lines.

III. The Neck – Transmission of Policy, Not Scrutiny

Every system needs a neck — a passageway to move things from one end to the other without thinking too hard about what’s in the pipeline. That’s exactly what the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) has become: not a filter, not a firewall — just a well-greased conduit for policy, pressure, and pre-approved outcomes.

From the outside, it looks like review. Inside, it’s relay.

The CNSC sits at the intersection of political mandate and industry ambition, where policy flows from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), through the Commission, and back out the other side as licensing approvals and regulatory green lights. If NRCan wants a new class of small modular reactors rolled out across the country, CNSC’s job isn’t to ask why — it’s to figure out how fast they can push it through without tripping over a consultation deadline.

Their contribution to the federal Small Modular Reactor (SMR) Action Plan says the quiet part out loud. CNSC staff didn’t just review it — they helped write it. A document intended to promote nuclear development had input from the body tasked with regulating it. That’s not independence. That’s a loyalty program.

And when industry wants to move faster — cut costs, reduce scrutiny, “streamline” the process — the CNSC doesn’t resist. It helps wordsmith the application.

“Our role is to support innovation while ensuring safety.”

Translation: Tell us what you’re building, and we’ll make sure the red tape doesn’t get in your way.

There is no meaningful tension here. There’s alignment. There’s compliance. There’s a regulator so deeply embedded in the cycle of promotion and project delivery that it sounds more like a nuclear venture fund than a public safeguard.

This is the neck of the regulatory centipede: flexible, responsive, and entirely unconcerned with whether the system is digesting poison — as long as the message reaches the mouth in time for the press conference.

And if you think that’s just cynical?

Browse their job postings sometime. It reads more like a project management firm than a public safety watchdog.

IV. Torso – The Contractor Complex

This is the gut of the beast — where public money meets private incentive, and oversight gets processed into quarterly returns.

At the core of the Chalk River NSDF is Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL), a contractor tasked with solving Canada’s multi-decade radioactive mess. But CNL isn’t a crown corporation. It’s run by Canadian National Energy Alliance (CNEA) — a for-profit consortium currently composed of SNC-Lavalin (rebranded as AtkinsRéalis), Fluor, and Jacobs.

Let’s pause there.

SNC-Lavalin.

The name alone triggers flashbacks: fraud charges, corruption scandals, bribery in Libya, deferred prosecution deals, and a political crisis that almost broke a Prime Minister. And now they’re helping bury radioactive waste upstream from the nation’s capital. Because of course they are.

The federal government contracted this group to reduce Canada’s “nuclear liabilities.” In theory, that means cleaning up messes. In practice, it means containment mounds, capped landfills, and just enough engineering language to pass regulatory muster. The faster they bury it, the faster they get paid. Public risk is eternal. Profit arrives in 30-day intervals.

CNL’s NSDF proposal would never fly in a country with functional institutional memory. Chalk River already has a legacy of radioactive contamination dating back to the 1950s. It’s located 1 kilometre from the Ottawa River. The site sits on porous soil. It’s seismically active. But somehow, the plan — a low-grade surface landfill for over 1 million cubic metres of radioactive waste — sailed through CNSC review with little more than a raised eyebrow.

Why?

Because the CNSC relies on technical data provided by CNL. That’s right — the company proposing the waste dump also wrote the documentation to justify it. CNSC’s role was to nod, reformat it into a public-facing PDF, and print some reassuring statements about “multiple containment barriers.”

Conflict of interest? Not on paper.

In reality? It’s a contractor-led safety theater where the fox designs the henhouse, writes the fire code, and bills the government for the eggs.

And to be clear, this isn’t a one-off. CNL has become the federal government’s go-to vendor for nuclear cleanup projects. Their mandate is to reduce long-term liability — not to ensure long-term safety. They’re incentivized to move quickly and keep costs down. That incentive bleeds into the entire regulatory ecosystem. It infects the language of risk. It shapes what gets tested, modeled, and scoped — and what doesn’t.

So when the CNSC says, “We’ve reviewed the evidence,” they mean: We read the proposal the contractor gave us, tweaked the verbs, and checked that no one was shouting too loudly in the footnotes.

This is the torso of the centipede:

A digestive organ for public risk, coated in corporate branding, and incentivized to metabolize catastrophe.

And when something leaks — because it always does — no one will remember who wrote what. Just that the approval was signed, the mound was built, and the contractors were already off-site by the time the groundwater got interesting.

V. Small Intestine – The Assessment Shell Game

This is where the digestion happens — slow, technical, and so buried in process that nobody notices what’s rotting underneath. It’s the CNSC’s favorite play: the environmental assessment, where risk is translated into abstract language, diced into categories, and eventually excreted as something “not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects.”

That phrase is the holy grail of Canadian regulatory bullshit. It’s been used to approve everything from toxic tailings ponds to offshore drilling. In the NSDF case, it was used to justify building a shallow radioactive landfill a stone’s throw from the Ottawa River. Because, apparently, burying over a million cubic metres of long-lived radioactive waste next to one of Canada’s most important waterways — in an area with known seismic activity and permeable soil — is just a minor landscaping project with a few extra warning signs.

Let’s unpack how the shell game works.

Step one: Let the proponent define the scope.

Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) wrote the core technical materials. They got to decide which risks mattered, how to frame them, and which modeling assumptions were “reasonable.” The CNSC accepted that framing almost wholesale — like a university prof grading an essay where the student also wrote the rubric.

Step two: Disaggregate the risks.

Flooding? Unlikely. Seismic events? Manageable. Containment failure? Engineered safeguards in place. But what about compound risks — the kind of catastrophic convergence that actually happens in real-world disasters? Not assessed. Why? Because the framework isn’t designed to test “what if this all goes wrong?” It’s designed to demonstrate plausible control.

Step three: Conclude that no single factor poses a “significant” adverse effect.

Voilà — project approved. And if anything does go wrong, future governments, courts, and taxpayers can pick through the radioactive rubble to find who said what.

You know what wasn’t thoroughly assessed?

- Long-term hydrology under climate change.

- The risk of groundwater infiltration over a 500+ year decay period.

- The inevitable degradation of containment materials decades after the contractors are gone.

But it looks good on paper. Lots of footnotes. Crisp formatting. You could mistake it for safety if you weren’t paying attention — which, let’s be honest, is part of the design.

This is the small intestine of the centipede:

slow, technical, and full of language that sounds nutritious while quietly starving the truth.

The CNSC doesn’t need to prove the NSDF is safe. It just needs to prove it’s not significantly unsafe by the narrowest, most abstract legal definition possible. And that’s what makes it dangerous — not just as a project, but as a regulatory template for future failures.

Because if this is the bar for radioactive containment in Canada,

we might as well start paving the next one now.

VI. Colon – Indigenous Consultation and Other ‘Waste Processes’

Every centipede has a colon — the part that filters out anything it can’t absorb and prepares it for disposal. That’s what Indigenous consultation looks like under the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC): a process designed not to incorporate dissent, but to manage it quietly until it can be flushed.

Take the Near Surface Disposal Facility (NSDF) at Chalk River. It’s being built on unceded Algonquin Anishinaabeg territory, directly impacting traditional lands and waters of multiple First Nations. Ten out of eleven Algonquin communities opposed the project. Some, like Kebaowek First Nation, filed extensive legal and technical submissions arguing the plan violated their rights — including the government’s duty to obtain Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) under UNDRIP, which Canada supposedly supports.

While UNDRIP is not yet fully codified in domestic law, Canada has committed to its principles, and the language of FPIC has been repeatedly invoked in federal reconciliation frameworks. The failure to act accordingly here reveals not just hypocrisy — but legal cowardice.

The CNSC’s response?

They noted the opposition, added it to an appendix, and moved forward anyway.

There was no serious effort to negotiate the project’s location, design, or long-term oversight. There was no equity in process or access to independent resources. There were briefings, forms, check-ins — bureaucratic rituals designed to simulate engagement while ensuring the outcome never changed.

This isn’t consultation. It’s containment.

The CNSC’s final decision claimed Indigenous engagement had been “adequate.” That word again — adequate — the Swiss Army knife of federal PR. It means nothing and is defensible only to people who’ve never had to drink from a river downstream of a nuclear waste mound.

What makes this worse is how the CNSC treats Indigenous knowledge. When cited, it’s as ornamentation. When inconvenient, it’s dismissed as emotional or anecdotal. The technical assessments — all provided by the contractor — are prioritized. Indigenous epistemologies? Acknowledged and sidelined, like a land acknowledgment given during a groundbreaking ceremony for the very project the community opposed.

And the government? Silent. Because this is the model. It’s not broken — it’s built this way. Consult, check the box, move the project forward. Displace the opposition with footnotes and filings.

If the CNSC was serious about respecting Indigenous sovereignty, this project never would have passed the smell test — let alone licensing. But it did. Because the colon doesn’t decide what’s important. It just decides what’s inconvenient.

This is how risk and resistance are processed in Canada’s nuclear regulatory system:

- Indigenous consent? Not required.

- Environmental risk? Disaggregated.

- Corporate timelines? Approved.

- Public opposition? Flushed.

And once it’s all been passed through the system?

It gets capped in clay and rebranded as “reconciliation.”

VII. Rectum – Public Communications and Reassurance

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission doesn’t just approve projects. It performs safety — like a stage magician with a clipboard and an infographic budget.

After the paperwork is signed, the assessments buried, and the consultation sanitized, the last stop in the centipede is messaging: the rectum of the system, where everything is polished for public release. This is the part where the CNSC leans into community “engagement” — glossy one-pagers, friendly Q&As, and YouTube videos with music that sounds like it was ripped from a mid-tier HR onboarding course.

“Canada’s approach to nuclear waste is among the most rigorous in the world.”

Translation: You’re not qualified to disagree, and we paid a consultant to make this sound reassuring.

The CNSC’s risk communication strategy is built around one central premise: if it sounds boring, it sounds safe. So they bury high-risk terms under an avalanche of technocratic euphemism. Radioactive material becomes “low-level waste.” Proximity to the Ottawa River becomes “within accepted hydrological tolerances.” Opposition becomes “considered feedback.”

And when people raise concerns — about cancer clusters, about groundwater contamination, about future generations drinking from what used to be a containment site — CNSC reps stick to the script. They cite “long-term monitoring programs” and “adaptive risk management strategies,” which, translated from bureaucrat to English, mean: “We’ll deal with it when it starts leaking.”

Even their public hearings are structurally tilted. You get five minutes. They get the entire system. You bring community testimony. They bring a legal team and a PowerPoint. And when it’s over, they thank you for your passion and file it next to “Communications – Handled.”

This isn’t transparency. It’s risk laundering with a customer service voice.

The CNSC doesn’t just fail to prevent disaster.

It makes you feel like questioning it is unpatriotic.

Like you’re the problem — not the radioactive landfill uphill from your water supply.

This is Canada’s nuclear reassurance strategy:

Deodorize the process, flush the dissent, and smile for the cameras.

VIII. Anus – Ministerial Oversight and Parliamentary Accountability

Every digestive system ends somewhere — and for the CNSC, that somewhere is the Minister of Natural Resources, currently the Honourable Jonathan Wilkinson. You might think this is where accountability lives. It’s not. It’s where it dies politely and is composted into funding announcements.

The CNSC reports to Parliament through this ministry — the same ministry tasked with promoting nuclear development in Canada. That’s not oversight. That’s a feedback loop. A regulatory ouroboros. A process where the same hand that writes the industry roadmap signs off on the “independent” review.

This structural rot isn’t even hidden. It’s proudly stated on government websites:

“The CNSC reports to Parliament through the Minister of Natural Resources.”

This is not a buffer. It’s a choke point — one that allows the federal government to distance itself from unpopular approvals while continuing to fast-track industry partnerships and public-private deals behind closed doors.

Parliamentary accountability, meanwhile, is more ritual than function. Most MPs don’t understand nuclear regulation. Why would they? It’s complex, expensive, and cloaked in jargon. That’s by design. So the few who try to press the issue are politely stonewalled with reassurances about international standards, best-in-class frameworks, and “confidence in the regulator.” That confidence is rarely based on performance. It’s based on not wanting to pick a fight with something that sounds technical.

And when it goes wrong — when the mound leaks, when the water’s poisoned, when Indigenous nations sue and win — the minister will express disappointment. The commission will announce a review. And everyone will insist the system functioned as intended, except the part where it didn’t.

This is the anus of the regulatory centipede: where everything that came before is released into the wild, responsibility is airbrushed, and whatever damage occurs is now your problem.

And unless you’re SNC-Lavalin, don’t expect a callback.

IX. Epilogue – Reversing the Centipede

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission is not broken. It is not underperforming. It is not out of step.

It is doing exactly what it was built to do:

translate risk into compliance, convert opposition into documentation, and pass liability downstream.

That’s not failure. That’s function.

The Near Surface Disposal Facility at Chalk River — a radioactive landfill on unceded land beside the Ottawa River — isn’t the exception. It’s the template. A fast-tracked project, approved by a regulator that answers to a promoter, based on assessments written by a contractor with a profit motive, pushed through over Indigenous objections, and wrapped in communications so polished you’d think they were marketing a resort.

If you’re still calling this oversight, you’re either willfully blind or comfortably bought.

Reforming this system isn’t about “restoring trust.” That assumes trust was deserved in the first place. It wasn’t.

It still isn’t.

What’s required is decoupling promotion from regulation, stripping oversight out of the ministerial digestive tract, and rewriting the entire process so it doesn’t produce a polished turd with a safety stamp on it.

Until then, the CNSC will keep doing what it’s built to do.

And if you listen closely to the next announcement, you might hear it:

The wet slap of the next approval sliding through the system.